Solarpunk: lenses and foundations

Posted on Tue 28 February 2023 in misc

Last year I published a lengthy videoessay on Solarpunk as a part of collaboration with a philosophical YouTube channel "Myśleć Głębiej" (Think That Through in English).

It took me a few months to translate it and update a few sections (especially regarding cyberpunk's romanticism), but I'd like to present you with a written form of my essay - available in audio HERE! The recorded form follows a deeper exploration of philosophy of the movement, thoroughly discussing the notions of cultural hieroglyphs and squeecore I only briefly mention in the text below:

Who am I?

My name is Pawel Ngei, on the internet also known as A-L-X-D. I’m a software developer and hacker, someone analysing technology outside of a formal framework of a company or university. I’m especially interested in cultural narratives about technology and engineering, their impacts on societies and communities.

I first encountered Solarpunk soon after the “Notes towards a Manifesto” came to be at Arizona State University in 2014 while looking for a way to express some values of the hacker movement I couldn’t convey to the general public. I was able to take part in some discussions and conferences with early creators within the movement like Adam Flynn and Andrew Dana Hudson. Last year I co-organized a fully remote online Solarpunk conference focusing on the voices from the Global South, called Solarisecon.

I’d like to tell you about this movement from a little different perspective than you might have already heard. I’m neither a writer nor a literary expert, but a hacker, technologist, who wants to understand what’s missing from our discourse about the tech and infrastructure around us and why we cannot express them in our languages and dreams of the future.

We might be able to notice much more about the world around us if we purposefully stand between the hard sciences, engineering and the social, literary perspectives, seeing how they influence each other.

A Solarpunk Story

To define what I’m talking about maybe let’s start with an example story – a story I consider the most Solarpunk of the ones I’ve heard, even if it’s pretty far away from most of what’s published in Solarpunk anthologies and magazines:

A deadly epidemic starts in one of the poorest countries of Africa. There are no vaccines or effective treatment for it – most of the infected die suffering and the only way to combat it is avoiding infection and studying the pathogen further. UN, WHO and Doctors Without Borders send their delegations / teams into the regions, set up field hospitals and want to help in any way possible.

The inhabitants of the region are terrified. Whoever has the means – and resources – flees it as fast and far away as possible. The people working in the banking and technological sectors who are left are barely holding the infrastructure together, not being able to count on any external help.

Faced with the overwhelming number of infections and tens of thousands of new medical workers – doctors, nurses, paramedics – the financial infrastructure, never very stable or effective – breaks down completely. Local military tries distributing physical banknotes, causing the inflation to skyrocket - soon, everyone starts weighing them instead of counting. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization sends people money, not food and medicines, which need to be bought locally. Without that - and the ability to pay salaries, medical personnel start striking, hospitals can hardly feed their own patients...

Seeing that they are going to starve faster than die of the new sickness, some patients escape hospitals, spreading the epidemic even further. With the paramedics on strike, bodies end up lying in the streets. The whole economy collapses and the country descends into chaos. Big corporations would love to help, but they cannot afford to send any people into the fray...

In the middle of all this, three local hackers-technologists contact international NGOs and the UN, claiming that they can stop the country from a total collapse by building an alternative payment system for medical workers, totally fair and transparent using Free Software and their second-hand laptops. They can promise that it will not be used to launder any money and everything will go straight to the emergency personnel. They only need permission. With some UN vouching, the president eventually accepts. What’s the worst that can happen?

To everyone’s surprise, the local programmers do exactly what they promised: in two weeks they create a fully transparent payment system, replacing the failing local infrastructure created by the big banks, allowing money transfers to the medical personnel and the continued operation of the field hospitals. With that in place, they organise teams registering medical personnel all across the country and making sure everything works. Inspired by their own success, the hackers start tackling other problems, fixing old and broken equipment in the hospitals, creating automated payment machines registering paramedics’ work without a need to remove their safety equipment or signing anything...

In the whole country, the medical system starts functioning again, people’s hope and faith in it overcoming their fear and chaos. Eventually, the epidemic gets under control. The initiative of the few technologists allowed the work of tens of thousands of medical personnel not to go to waste. Together, they created a miracle, saving hundreds of thousands, if not millions of lives.

So we have an epidemic (many of which we will have to face because of the climate catastrophe), we have the weakness of the huge structures (the local government, corporations, even the UN), we have local activists and independent, open technologies creating sustainable solutions. We are seeing a perspective from an African region usually ignored in our discourse about the future – and the present. There’s conflict, tension, drama – and yes, you could probably write it with a little better pacing – and try making it more real, because who would believe that three local guys from Africa can achieve something huge that international corporations cannot?

It’s not a well-crafted story, it could use a lot more work before it would land in some anthology. The author has some potential, though.

The problem is: this story has no author. It’s not a piece of feel-good fiction, but a very real story from Sierra Leone and the whole West Africa besieged by the Ebola epidemic in 2014.

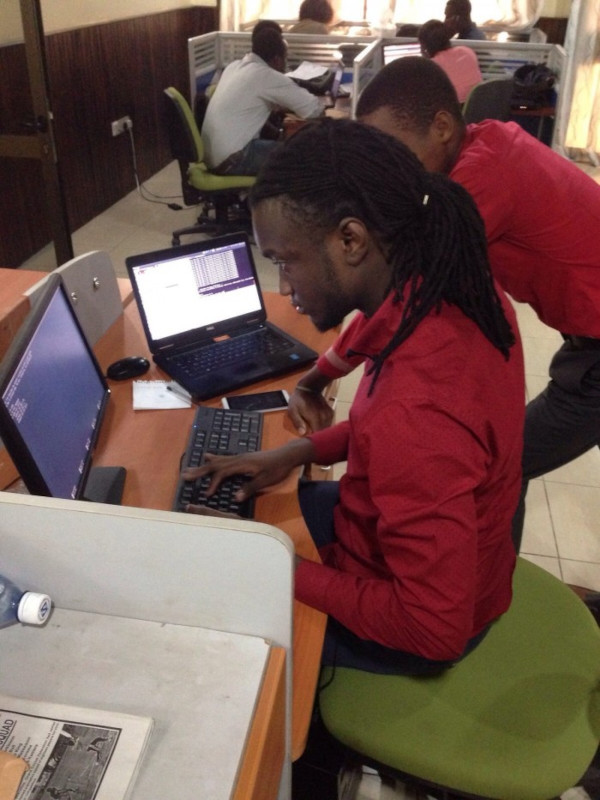

iDT Labs Salton Massally

The local guys from IDT Labs’ names are Salton Arthur Massally, Harold Valentine Mac-Saidu and Francis Banguara. They exist, you can find their social media handles or send them an email. They really saved hundreds of thousands, if not millions of lives.

Why haven’t you heard about them, you could ask? Their story did get covered – a few paragraphs in the Guardian and a talk at a German hacker conference. It didn’t get too far in the mainstream media, though. It’s too alien. Too hard to imagine. It’s not possible that some random hackers from Sierra Leone could replace their national banking infrastructure (originally created by the great minds of the West!) in just two weeks! Even if they actually did it.

Years later, the heroes from the iDT Labs got some recognition in the United Kingdom: they got a Responsible Business Award. I think the problem with describing their work is very visible in the telling words of one of the judges from the contest:

Think about it: this company actually stopped their core business, even though they were a software developing company, solutions developing company. They stopped their main business and they dedicated all their resources to come up with this because they actually believed and they saw that they needed to do this for their country. You know their country was about to collapse and they needed to do this.

As much as I agree with the significance of their work, I am absolutely terrified by a perspective of the world where saving lives is something unexpected, something extra, while a regular company should just… continue production and regular functioning not to lose what is the most important: money and profits.

Solarpunk as a perspective

For me, this shows one extremely important thing: our current culture, caught between neoliberalism, postmodernism, cyberpunk and postapocalyptic narratives, however you want to call them – makes us blind to what is happening around us. We cannot see or describe real events around us which could contradict the mainstream narrative, could get us out of cultural biases which force us into the ever-present escapism and fatalism.

Solarpunk is not just a theoretical set of themes, tropes, aesthetics with a few anthologies published. It’s a perspective which allows us to see more in the world around us, discover that no, we are not living in cyberpunk, we just accepted such a narrative and normalised its values in our societies. We expect the huge corporations to spy on us, the labour unions to be pointless and hopeless, that any fight against power is unwinnable.

What can we do then, to imagine different, better futures, which wouldn’t be alien and incomprehensible, too big to convey in a single story or image? As you heard before from Think That Through, we will need hieroglyphs: consistent and concise visions of narratives, aesthetics and worlds, like Asimov’s robots, cyberpunk’s prosthetics or steampunk airships.

To be able to tell stories without explaining the whole history of our world, its systems and cultures, we need to use hieroglyphs which our readers, audiences already know from other media. They know what to expect, so we don’t need to create boring exposition dumps, suggesting the implications of faster-than-light travel for our planet.

The same way our real-world stereotypes about different nations, genders and ethnic groups can be harmful – the cognitive schemas from fictional stories can be projected upon the real world. If we keep watching stories which make some behaviours and ideas seem impossible, eventually we will stop imagining them as realistic in our daily lives!

The superhero cinema forces a lot of invisible assumptions and ideas into every movie. It’s not only about fighting to maintain the status quo, but about the possibilities of what lies beyond. Every more technologically advanced society you’ve seen in recent years – be it Atlantis, Wakanda or Asgard – is governed by a system less socially progressive than ours, implying that social and technological progress are somehow disjointed. Fed with that, we slowly stop expecting that society can evolve along with technology.

What’s more, we start seeing the technologies themselves only as they are presented: as weapons, single-instance artefacts, never infrastructure you could share or modify. Watching the Iron Man we don’t ask ourselves why he’s not using his Arc Reactors to replace gas and coal, to combat climate change. This would be too unimaginable.

The same way we are taught to see every nuclear technology as a potential weapon, not an energy source, making us never imagine that there might exist real reactor technologies which can’t be weaponized, which don’t have meltdowns. We don’t want people asking their governments about funding such research now, do we?

Since Solarpunk is not a popular genre yet, it doesn’t have the hieroglyphs, visual and narrative themes which could lay seeds in our imagination. It cannot turn our attention to the real world around us and allow us to see it differently, with more hope. Until we all have easy access to Solarpunk books and movies giving us the vital context, real stories like the one from Sierra Leone will be impossible to report, too alien, unnatural and too far away from what we’re taught to expect.

That’s why the creation of the symbols, hieroglyphs and aesthetics is so important: it’s not just an idle game of bored writers trying to find a new niche, but a very conscious social project, a type of activism aiming to convince the society that we can see the world differently. Making us imagine worlds better – and not less possible – than our own.

Solarpunk and neural networks

If you searched for anything Solarpunk on the Internet, you might have found scores and scores of images created by neural networks: green skyscrapers, bubble-greenhouses, solarized landscapes. In such a crowd it might take a while until you see something created by a human artist – but it will be visibly distinct, not only because of the correct number of fingers.

There are quite a few interesting thoughts to unpack -

We could start by looking at the ethics of neural networks, devouring work of thousands of artists without permission, generating money for whichever company or corporation owns it, proclaiming some kind of “democratization” as they only centralize more and more power, forcing the rest of us even lower. There was a lot written on the topic already – and no, I don’t believe that any corporate-owned AI can be Solarpunk.

What is even more interesting though is the blandness and unimaginativeness of the neural network works. Thanks to them you can spot what I just discussed: the absolute lack of hieroglyphs, visual language and symbols. The “AIs” recycle what they have already seen, without any creativity and intent, so they imagine: our old symbols of the future, but greener. With the sun in the background. If they just ate some non-European gallery, maybe there will be a tuk-tuk somewhere?

This not only emphasizes how important it is that it’s a human, intentional artist, who can create a hieroglyph-prototype, but also shows us what is missing from our popular culture. The neural networks “ate” a lot of popular galleries, which – consciously or not – lacked a lot of symbols or hieroglyphs. Our popular culture is devoid of visual marks for a “community” or sustainable architecture. It’s not the neural networks’ fault that they cannot imagine Solarpunk: it hasn’t been properly introduced yet.

We can also take a look at the notion of “defaultness” beautifully exemplified by the graphical networks: the less you specify the image you are looking for, the more standard, popular, stereotypical and biased it will get. Ask for a scientist. How many of them are women? Ask for a woman. How many of them are Caucasian? How many of them will be pretty teenagers, how many average, realistic, older? The more you specify a person – especially venturing into the Global South, or away from the pretty actors and actresses – the more… random and alien the results will be, with weird fingers, ears, double necks and so on. The neural networks “ate” so few of such examples that they’re struggling to imagine them!

Again, it’s not a feature of the neural network. It’s the feature of its training sets, of our popular culture, showcasing us what we are blind to, who we can’t imagine, what symbols are missing. If I was to say what is a use for a graphical “AI”, I would say that: exploring our blind spots, seeing what symbols need to be crafted and forged by an intentional artist.

Very similar things can be said about text-based neural network, mimicking the form, blind to the contents and meaning of the paragraphs they spew out. They are as sexist, racist and xenophobic as the texts they learned from, without any critical thought as to what they’re repeating.

I tried asking one of them for a Solarpunk story and I got several permutations of the same thing: a [community] is [brave] by [installing solar panels]. Sometimes there’s a sci-fi or fantasy spin, some rebel, evil queen, lost civilization. No notions of relations between the members of the community, between different communities or their values. These weren’t in the training set – and will need to be crafted separately, intentionally.

That’s why I am not worried about the artists being culturally replaced by the neural networks, even though I’m sure the corporations will try to replace them commercially to centralize more of their power. Only a human can have an intent, create a new meaning, a hieroglyph to start meaning something, to be shared to mean this-whole-new-beautiful-vision.

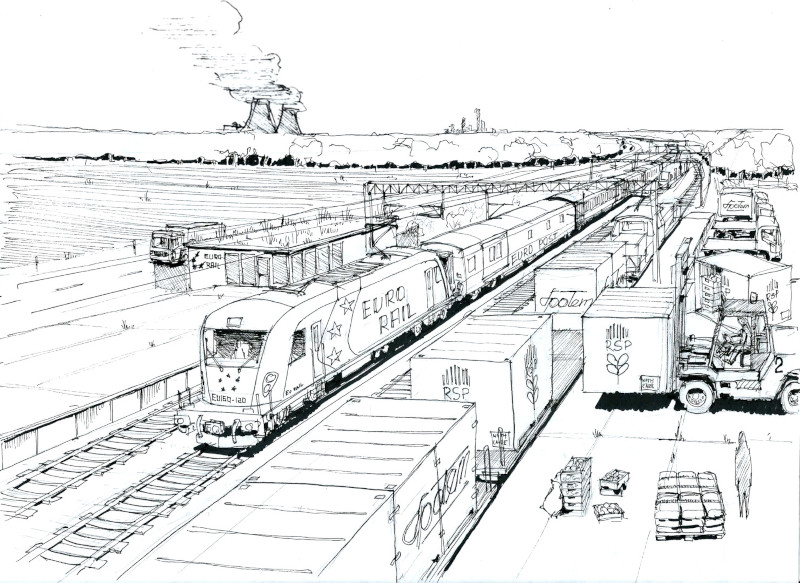

I worked with many visual artists trying to convey Solarpunk in their art. Recently I joined forces with an architectural student who wanted to imagine a greener, sustainable and socially just future for Poland. He didn’t want to just copy-paste some Art Nouveau, but really thought about it: created an illustration of a train being loaded with small containers from independent farming coops, among bike paths and pedestrian architecture.

It would be a perfect illustration for a story explaining everything there, but seen without such context – not hidden under a hieroglyph already – most people see just “a colorful train”. We’re not trained to see or expect some things, so we just gloss over them.

Sustainability

If we would like to venture even further, we could look at language itself! Most of Solarpunk is created in English, with some books available in Portuguese, Spanish and Italian.

As the movement itself celebrates diversity, there are writers and editors concerned by the primacy of English – like Francesco Verso, who made it his mission to translate multiple anthologies to languages other than our current lingua franca, to convey meanings which can escape it.

English is not the only language missing meanings and terms, though. Because of the primacy of capitalism and corporate ideologies, some languages which didn’t have the word for “sustainability” before the 1970s, never developed one!

Polish is one such example, where officially “sustainability” translates to a very corporate “balanced development”. A whole slew of concepts, so natural and so VITAL for Solarpunk are suddenly unexpressable, because in Polish, things cannot be sustainable without being further developed, grown and capitalized upon.

One of the missions of Solarpunks in Poland is to propose a new word for sustainability, like “odżywalność”, following similar Slavic concepts, coming closer to homeostasis, life and rebirth. It will take a lot of work, but it can certainly be a milestone and a symbol, a very concrete and visible hieroglyph leading all the others to come.

Other languages have similar blindspots, missing words like degrowth – and English itself could learn a thing or two from them, stepping away from colonial and imperial intellectual barriers.

Mediocre stories

As many Solarpunk critics note, most books and anthologies intentionally calling themselves Solarpunk are not widely known, mediocre, or… somehow artificial. Despite Becky Chambers’ Hugo Award, we still don’t have a single Masterpiece to unify all Solarpunk values and create a set of hieroglyphs to inspire others. We have a dozen - often conflicting – philosophies and manifestos and the whole cultural movement seems to be driven more by theorists rather than writers and artists.

Despite the monumental work of Becky Chambers, Francesco Verso, Sarena Ulibarri, Ruthanna Emrys and LX Beckett – a lot of the above accusations are true. No single Masterpiece so far inspired dozens of artists with its language and hieroglyphs. I don’t know if such a plain mimicking and remixing of symbols wouldn’t hurt Solarpunk: the movement defines itself by its will to self-reflect, using tropes and symbols consciously. We don’t want to end up greenwashing or repeating harmful narratives just to “be a part of something”.

Otherwise, why wouldn’t we take a page from the Steampunk’s book and paint a Solarpunk aristocracy, basking in art nouveau? Why not focus on the magical greenery, solar panels, let the aesthetics flow, write a well-crafted book in a familiar form, which would easily get popular? The problem is: by blindly repeating such a trope, we will totally lose our drive to envision a better world, instead repeating all the problems that consciously-or-not emerge from it. Aristocracy, while radiating beauty, implies an underclass.

Every Solarpunk story is therefore a very intentional prototype of a hieroglyph, often clumsy and unintuitive. It’s an attempt of creating a symbol which will not lead us to the old tracks, but propose a new, unexplored path. It’s a seed which can sprout into some solid roots in the popular imagination – or wither.

When criticizing Solarpunk’s awkwardness it’s also worth realizing that most of the stories, books and anthologies we read are... published. This means that they were not only – edited – as in had their grammar and spelling checked – but they went through a strong filter deciding which story is “marketable” and which is not.

Thinking about it this way, it’s rather obvious: the editors want to publish only things that will sell. They don’t reject only books badly written or boring, but also the ones which could be too alien, too hard to understand. What Jay Springett calls “cultural fracking” – it’s a much more financially sound decision to publish a sequel, something reusing already known tropes, than to experiment with something new. This leads us again to Squeecore about which you already heard from Think That Through.

Being a technologist myself, I had a lot of opportunities to help artists, writers and playwrights do research for their current projects. I showed them real technologies, problems they solve and cause, the tensions and drama arising from the invisible infrastructure around us. It was a very interesting experience, as it allowed me to see how many of those projects were rejected by the editors and publishers. Even if the craft of the book, story, script was good, it was deemed too alien, as it didn't use the familiar cyberpunk tropes or a typical externalized conflict.

A few years ago I was asked to help write a TV series about hackers fighting pedophiles online. What was initially a series of car chases and cyber duels by some mask-wearing lone wolves, was eventually reforged into a deeper narrative about a society and communities. The boss of the pedophile group no longer approached children in chat rooms – instead he was a philanthropist giving away notebooks to poor, vulnerable children, so that they could use the Internet at home. No teacher or librarian even considered checking them for malware, which gave the pedophiles access to their machines and webcams, which allowed the group to function with industrial efficiency. The hackers in the series – instead of punk cyber-jockeys, became activists, trying to convince the local authorities to scan the gifted computers, talk to the kids and teach them the basics of privacy and security. The conflicts became much more multi-dimensional, social and sociological – with the car chase on top. Yet, the whole idea was deemed too… non-standard, too alien for an average audience – and not worth considering for production.

The variety of stories we can tell is limited even by our over-reliance on the Hero’s Journey, taught in most schools as applying to all the myths, legends and play across all the cultures of the world. The main character needs to be proactive, change across the three-to-five acts, have a darkest moment etc etc.

If you’re looking for a narrative structure putting a community in the spotlight instead of a single character, you will struggle with most of the western writing handbooks or TVTropes. We have some notes of groups, teams, one-chapter-a-perspective, maybe even characters representing a whole social class, but still, the stories from Southeast Asia, South America or Africa appear ridiculously alien and weird. A passive hero? No tragedy of the commons? Everything we learned at writing schools teaches us that this is wrong, that our basic biology expects a different story structure, so if people from those cultures like theirs, maybe we can force it into a Hero’s Journey... somehow?

Many Solarpunk writers are aware of this and want to actively explore different narratives and plot types, openly prototyping and exploring how it affects not only the reception, but also the dynamics between the characters and communities, their conflicts, types of violence – emotional as often as physical – and drama in general. A lot of such stories, while brilliant, will not be published in a magazine or an anthology and only the most recognized authors will be able to get such a book past the editorial board.

Where’s all the drama?

Prototyping alone, you can ask where is the drama in Solarpunk stories, where’s the exciting story? Many people point out that it’s hard to introduce tension in an already-established utopia, where every battle has been won, the climate stable, civilization – sustainable and everyone – happy. Why would we need postcards from a paradise?

Totally ignoring the inspirational and motivational value of such a postcard, it’s worth noting that our cultural tendency to disbelieve visions of flawless places was explored by Ursula Le Guin herself, in her “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”. If something appears good and doesn’t have a hidden dark secret… it’s suspicious.

Some of the Solarpunk creators and researchers propose divisions of the genre into the three “ages”: the “pre-Solarpunk”, a world in which the ideas and hieroglyphs are only beginning to develop, like today – the “Solarpunk”, in which the clash between the narratives and perspectives becomes mainstream and influences the shape of the civilization – and the “post-Solarpunk”, in which its ideas have already won and the utopia is (fully?) realized.

A lot of already published books and anthologies could be classified as the last category for a few reasons: Firstly, it’s much easier to inspire others with a vision of a world already materialized, with values already internalized by its societies, where we can show them working in practice. Secondly, it’s much easier to publish something less “gritty” and polarizing or commenting on very real politics. Thirdly, just attempting to imagine a path from “here” to such an utopia requires an astounding amount of knowledge in many fields; risky hypotheses about economies, cultures, societies and climate – all of which could easily become outdated and straight-on ridiculous. Post-solarpunk is then a much safer bet to get your story published.

Personally, I prefer the second era: Solarpunk, the Time of Changes, the clash of ideas, trying to deal with problems in ways which are currently unimaginable. It’s a dirty and practical future, often much less inspiring, more tired and full of failure, burnout, but with a lot of hope underneath it all. Such a vision acknowledges the whole upcoming trauma of climate change – and the fact that we will not Magically All Get Along, but will need to fight thousands, millions of smaller battles to save a local community, culture, ecosystem. It showcases the daily lives, agency and identities of the inhabitants of each small region of our planet.

My Solarpunk is full of stories inspired by thousands and thousands of real-world reports of what’s currently invisible: refugee camps turning into bustling cities with their own creoles and cultures, the traumas of millions of miners losing their jobs, experts racing with time to convince the general population to give up their old habits before a new disaster strikes. I see those stories as dripping with drama, conflict, even without a single villain, just zooming on the friction between different interest groups sharing the same goal. And even with this all – each of those stories can carry the special Solarpunk hope, the beauty of working together, the belief that tomorrow can be better.

A few years ago I was approached by teachers from Poland trying to encourage their writing students to create such stories – they were struggling, not seeing the drama where the popular culture didn’t prepare them to see it. Together we decided to create a list of 22 story hooks for them, to easier see the trauma-and-hope typical to Solarpunk. Now, thanks to the huge help of Tomasino, we created a Solarpunk Prompts podcast presenting each of them in 10-15 minutes.

I’ve spoken about these prompts with many writers and I’ve begun to realize that a big part of why so many people are resistant to writing Solarpunk is that it requires you to acknowledge the upcoming trauma. While the current popular culture wants you to escape in some fantasy world or straight-up give up, surrendering any responsibility, Solarpunk wants you to admit that we will all suffer. We need to process that, without rationalizing or romanticizing it. Only once we do, once we can hold this unpleasant emotion in ourselves – we can begin to see hope beyond it, the hope which allows us to rebuild, not just a naive fairy tale.

I’m sure that there are some deep observations to be made about which authors – or cultures – are already prepared for such trauma – but I do not feel qualified to make them.

Seeing this, we could ask ourselves what’s utopian in Solarpunk? Is this a world in which every battle has been won? Now beautiful, just and stagnant, a diverse, anarchist society, with no violence, no conflicts, no miscommunications?

I think anyone who had any experience with an anarchist community – or even working just in groups – can attest to the absurdity of the image. Working together without miscommunications, arguing over values, hurt feelings? Without quarrelling over the tiniest detail and the most important axioms? In my opinion any attempt to imagine a world without toxic hierarchies must be full of dynamic tensions and conflicts, trying to convince each other, without a quarrelsome social homeostasis. If you want a good example of such a story, I heavily recommend Ruthanna Emrys’ “Half-Built Garden”, in which most of the plot is built on this exact notion.

If I could propose a different definition of utopia for Solarpunk: it’s a world in which everyone acknowledges the problems we’re facing: the climate change, unsustainability of our technologies, economies and civilization – and in which everyone agrees to act on that. They don’t need to agree on specific steps to take, but they are ready to discuss it.

This is a vision of the world I aspire to: one without rejecting reality, without violence trying to silence someone. This is my inspiration for the future.

Where’s the punk in that?

Okay, but where is the -punk- in all that? It was supposed to be SolarPUNK, not a sunny everyone-get-along-now! Where’s throwing molotov cocktails at hypercorps, where are the mohawks and being the underdogs? What’s punk in starting a garden?

What if I tell you that Solarpunk is a bigger punk than everything above, more than all those runners and street samurai of cyberpunk, because it rejects not only the corporate world, but also the tired mode of rebellion propagated by our popular culture?

All the visions of the dark future from the last forty, fifty years got us used to a dichotomy: bad corporations, their wage-slaves faithfully serving their rich masters hoping for a payday versus hackers-rebels, living outside of the system, eternally at war with the corps and their servants. It’s a hopeless war. If it’s ever winnable, it will be a pyrrhic, temporary win, because a lone cowboy can’t shoot the whole system. It’s even worse, because often to achieve such a “win”, they must become a part of it, replicating the same toxic structures, hurting others.

It’s worth noting that in cyberpunk stories – even Mr Robot – the victims of the rebels are not only the rich and powerful, but often innocent bystanders. We are supposed to internalize that the fight is immoral in itself, the anarchists are dangerous and about to hurt us. All they do is fight, sabotage and destroy after all.

We never see them build anything.

Even if they do, it’s always desperate, a temporary haven, just a tool for their war against The System, the corps, the fascist state. They cannot build, or propose anything outside of it, outside of the dichotomy, the model of a rebellion which was already co-opted by the corrupted world.

The same way we are unable to imagine just… walking away and building something outside of it. We’re absolutely blind to the real world, when we see others doing exactly that.

Many people will argue that we need to imagine the fights ahead, that change will not be painless – and I agree. The problem doesn’t lie here.

The way I see it, cyberpunk romanticizes oppression, fight and struggle. It doesn’t want to show us the world worth fighting for, it wants us to revel in being crushed and rebelling, because virtue doesn’t lie in finding a way out, it lies in participating in this fight.

What’s a win state for cyberpunk characters? Who are the ones others tell stories about? It’s the martyrs. Cyberpunk glorifies the rebellion to the point of expecting some kind of cyber-valhalla (it’s so cool), blinding us with awesome neons, shiny chrome, making us forget we can do something else.

For me the best indicator of whether a narrative is Solarpunk is a simple question: can it portray Wikipedia, as a project? Not a means to fight The System, not a tool for manipulation of the masses by the corps and the government, but as a Great Civilizational Project.

Because for me, Wikipedia, despite being flawed and imperfect – is a Great Project. It’s something that generations of science fiction writers dreamed about: THE Great Encyclopedia, containing (almost) the totality of human knowledge, available to everyone, for free, at any moment. Built by every one of us, as an Editor, Researcher, Scientist, where it’s our communities editing and improving it, arguing and building consensus. It’s a success for the whole civilization, a Wonder of the World, impossible to imagine if it didn’t exist in the first place.

It’s so unimaginable that even today, we cannot tell stories about it, because we lack the hieroglyphs! We cannot see the librarians as heroes! Teaching, sharing knowledge, archiving the history of your language and region before it’s too late cannot be dramatic!

In my opinion, that’s where the -Punk- lies in Solarpunk: in building alternatives instead of taking part in a hopeless struggle. In not allowing to be written into someone else’s narrative, to become a safe – predictable – rebel. It’s accepting the grassroot movements, collaboration with all its conflicts, imperfections, as something beautiful and worth telling stories about.

Move quietly and plant things. A quiet work of thousands, millions of people working towards a better tomorrow, towards alternatives, planting small seeds of hope and improving the world bit by bit, to grow a forest which will sprout with the power of millions of trees. Scientists and engineers working on free software, activists trying to convince the unconvinced, educators sharing knowledge: people believing in new narratives, punk- towards punks who got stuck in their old battles.

And with that, suddenly, we can see all the real stories we haven’t noticed before, all of them more Solarpunk than many volumes of anthologies -

When the nuclear reactor in Fukushima, Japan, suffered a meltdown following an earthquake in 2011, the governmental infrastructure and response systems weren’t ready. In the whole region there were only a few radiation monitoring stations with data available to the responders – they couldn’t say which areas were contaminated and which were not. In panic, the government moved people from practically untouched zone to a much more dangerous region.

In the following weeks not everyone responded with anti-nuclear panic, though. A group of local hackers and technologists created a “Safecast”, radiation counter connected with a GPS module, which automatically uploaded their measurement to a map, creating radiation gradients precise up to one metre. The activists gave the devices away to people from the region, and then the whole of Japan, who meticulously mapped the contamination more precisely than the best military or scientific organisations. Everything was based on free software and open technologies, without any surveillance or reliance on any private business attempting to commercialise the project.

Inspired by the success, citizen scientists from all around the world started using Safecasts to map their own countries, be it on foot, on bicycle, by driving a car or riding a train.

In my opinion, this is the punk we were looking for.

What to read, how to live?!

Coming back to books, anthologies and magazines -

A lot of people starting their Solarpunk journey with Becky Chambers’ Hugo-award-winning “Psalm for the Wild-built” may see it as a very philosophical book, beautiful in its own right, but not very connected to our current problems, not offering the hope we so desperately need. For them, I have a few recommendations, not in any particular order:

The first is "Walkaway" by Cory Doctorow, who like me is a hacker and technologist first and foremost. While his perspective on culture and society might strike you as very peculiar, most of his books are the “next Tuesday science-fiction”, focused on here-and-now, not a world in a thousand years. I don’t want to spoil too much of the Walkaway, but half of it is Solarpunk, focused on building alternatives to our current civilization – and the other half is post-Cyberpunk, coming back to the conflict on very different terms.

The characters from the book decide to leave the capitalist cities (the titular Walkaway) and create their own, sustainable outposts using open technologies. They use real-life open source blueprints published by the UN and NGOs around it, originally for Global South refugees, not people giving up the comforts of the city. The characters create their own communities, learn how to get closer to each other and share their hopes and fears building something new together. They collaborate with other outposts all around the world, avoiding hierarchies and violence. If they cannot agree to what they see around them, they have again – the right to Walk Away.

Cory Doctorow notices how much drama can be seen in the times of change: he sketches the characters who wholeheartedly want to build a better world, and yet are limited by their very human flaws, traumatic pasts, prone to conflicts and quarrels. In time, together they work out a plan for something much bigger than themselves – and the outside world comes back, not willing to forget about them. The conflict intensifies, adding new layers, straying further and further away from mere philosophical musings. The hope in Walkaway stems not from a vision of peace, but the conviction that even the biggest challenge can be overcome together.

Ruthanna Emrys paints a similarly bold vision in her Half-Built Garden, envisioning a world between the age of Solarpunk and post-Solarpunk, slowly regenerating environmentally and settling into a new social balance between the new eco-anarchist majorities, old governments and remnants of the corporations. What sounds like a setup for a war gets interrupted by a staple trope of a bygone era: the First Contact with another civilization, this time not handled by the Communists or Capitalists, but a young mother, water sensor technician, carrying her baby in a sling as she is about to run some maintenance.

While not being perfect, the Garden impressed me with framing its conflict, making it clear that it cannot be violent: it must be resolved diplomatically, or everyone loses. Despite the stakes being very global, the story is deeply personal, maybe even to the point of irrelevance of some of its subplots.

I really appreciate the weight Ruthanna Emrys puts on the most important technology in her world: the social-and-technological network which allows people to reach consensus and move forward with their decisions. It’s not a representative democracy, not a meritocracy, but a transparent system which includes everyone.

The Garden touches on one more important issue of Solarpunk interest: the shape, meaning and function of the family, be it blood or found. It not only includes different definitions of gender roles, but openly asks a lot of questions – which I will not spoil.

If you’re interested in transparency, LX Beckett’ "Gamechanger" has a bold proposal: it’s a story of the whole civilization, almost collapsed in The Setback (what an euphemism), now rebuilding in a very different way.

Following several characters, we can see daring proposals, slowly painting a cohesive image of a very different – but still recognizable – world. After the age of social networks there was no putting the cat back in the bag – every information about everyone is public, making corruption much, much harder. The currencies are based on sequestered carbon – making intercontinental flights virtually unaffordable, allowed only in the greatest emergencies. The private property is almost totally gone, with everyone equipped in a toothbrush and a computer terminal only. The housing is managed by local communities, assigned according to needs - but it’s not a communist asceticism! Everyone is free to decorate their place in ubiquitous AR and VR, inviting over friends from all over the world, so close despite the travel being so expensive. People share experiences gaming, going to clubs and concerts – and the gamification, previously serving capitalist addictions, now motivates everyone to care about their surroundings, watering the plants in the public park or remotely piloting a farming drone at the other side of the globe.

Whether this world is a utopia or a dystopia is up to you to judge. What I appreciate is the boldness of the proposal, a world which doesn’t shy away from changes, a prototype of a world bigger and more complex than a lot of the shorter stories you can find elsewhere.

There are a lot more visions equally deep and ambitious, offering us solid new hieroglyphs to analyze, reuse and embrace – or discard as something not useful, ill-fitting or ineffective. Do we really want to imagine a future without privacy? Are biotechnologies more important than material engineering? What is the place of an individual within a society, a community?

Solarpunk Worldwide

To fully outline and understand Solarpunk we need to notice one more, extremely important aspect: its willingness to look outside of the West, allowing people from all over the world, especially the Global South, to tell their own stories and share their local problems and perspectives. Solarpunk futures are not just globalised cities in the US or China, but also the communities of Malaysia, Colombia, Burkina Faso or Czechia.

Every region has its own problems and solutions, which might not work somewhere else. There’s no point in comprehensive heating infrastructure in Kenya, while Poland doesn’t need to prepare for earthquakes.

The same way every culture, society and community may want to paint its own vision of the future, working together with others and sharing knowledge, but not losing its own identity in a globalised soup. Solarpunk wants to create a space for that, invite them to a debate, a multi-voiced chorus of ideas and dreams.

While in the global, English-speaking culture there are very few near sci-fi books tackling the real problems - like the climate changes - there are even fewer such works from the Global South. Many postcolonial countries are struggling with finding a new narrative for themselves, especially given the economics of the publishing market. It’s much, much easier to sell an African poverty porn story than a dream of independence and a hopeful, sustainable future from the continent.

Even outside of that, a lot of regions have their identities, cultures coupled with technologies which are becoming more and more obsolete, like Polish Silesia and its coal mining. Most local writers feel much safer in repeating cyberpunk dystopias set in local languages and aesthetics, unwilling to create a bold and realistic vision of the region transitioning out, knowing all the trauma needed to be processed for that.

Solarpunk encourages us not to resist what’s inevitable and to embrace change, prepare for it by envisioning who we might be afterwards, towards what future we could go forward.

We will need a lot of prototypes, some of them naive, some of them counterproductive, but nonetheless worth working on so that we can try out what works and what doesn’t. We should still be wary about accepting something without knowing its context, especially if the representation might be superficial, like Marvel’s Wakanda - being more of an Afro-American dream of their utopian Atlantis than an actual dream of anyone from the Sub Saharan region.

Let’s hear the actual voices from all over the world, not only those filtered by western film schools and universities. I’ve already seen an East African take on Ghost in the Shell, people musing about a Nigerian high school anime - and let’s not forget the very first Solarpunk anthology, which came to us from Brazil!

Summary and the definition, again

Wrapping up my essay, I’d just like to reemphasize two of the thoughts I consider the most important in it:

Firstly, Solarpunk is both a lens with which we can see more of the real world, otherwise invisible and easy to ignore – and a foundation, a series of prototypes upon which we can build a new language with which we can describe a better tomorrow.

Secondly, such an utopia doesn’t need to be a static and boring paradise - it can be a dynamic and dramatic homeostasis full of tensions. The utopianism may lie in the fact that everyone acknowledges the problems around and works toward solving them, sharing a will to overcome conflicts.

Such is the Solarpunk I would like to create and read – and such is the Solarpunk I wish you all.